OBSIDIAN BUTTE

IMPERIAL COUNTY,

SOUTHEASTERN CALIFORNIA

![]()

Obsidian Butte, (CA-IMP-245) in Imperial County, California, part of the Salton Butte complex has been extensively studied geologically, in part due to its location on the San Andreas fault, and partly due to the construction of the geothermal plant nearby (Robinson et al. 1976; Schmitt et al. 2013; Wright et al. 2015). This prehistorically popular, somewhat vitrophyric, obsidian source was originally covered in fine detail by Richard Hughes (1986), although it was not ground-truthed in the field by Hughes. We have a good source standard data library for this source at Albuquerque, and routinely analyze archaeological collections from San Diego, Imperial, and Riverside Counties. In December 2009 the samples originally collected in the 1980s were re-analyzed on the ThermoScientific Quant'X for both oxides and trace elements (Tables 1 and 2). This mildly peralkaline obsidian exhibits a unique elemental composition in the region (Hughes and True 1985; Panich et al. 2017).

In October 2017, Obsidian Butte was revisited, re-sampled, and mapped. Modern earth moving, possibly in association with geothermal investigations in the area, have extensively impacted the site. There is no certain archaeological evidence at the locality, and there has been extensive recent collecting of the obsidian at each of the three vents or domes. The purpose in 2017 was to sample each of the domes in order to obtain a more complete picture of the elemental variability of the source (see Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 1 through 3 below).

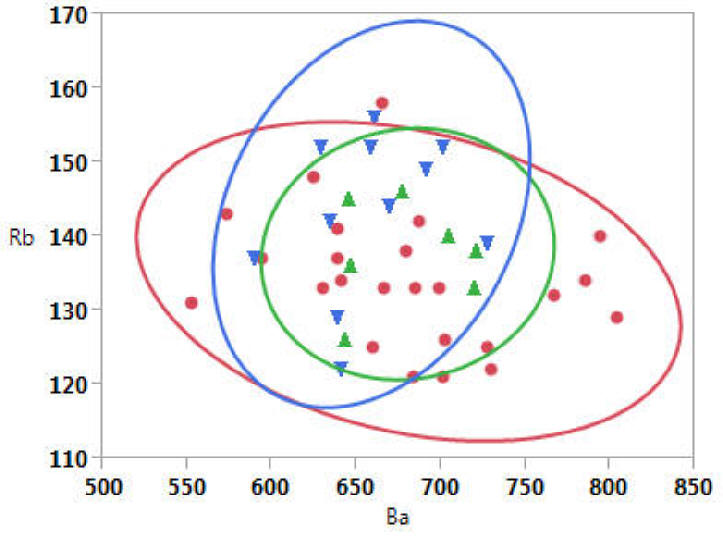

While all the Obsidian Butte domes produced vitrophyric obsidian with relatively sparse sanidine (alkali-feldspar) phenocrysts and some with larger spherulites, the vitrophyric quality was not enough to prevent the production of projectile points, some well executed including keyhole notching and serrations (McDonald 1997; Shackley 2017; see Figure 4). As eluded to by True's early (1970) study in the northern Peninsular Ranges (Cuyamaca Rancho State Park) in eastern San Diego County, Obsidian Butte obsidian is quite common in the mountain sites, and was distributed throughout Kumeyaay territory by exchange that occurred during the fall acorn harvest and deer hunting (see Shackley 2004, 2017). The obsidian is a brittle raw material that knaps quite easily, but my experience at the source suggests that some selection is necessary - some material is more brittle and/or vitrophyric than others. The obsidian at the smaller western butte (101917-3; see Figure 1), appears to be somewhat less vitrophyric, and could have been the dome where most prehistoric quarrying occurred. It is impossible to see certain evidence of prehistoric quarrying today, and the elemental composition of the three buttes is statistically similar and cannot be discriminated by XRF (see Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 2 and 3).

Early investigations suggested that the source was 30,000 years old (Robinson et al. 1976). Recent research, and archaeologically important, indicates that the obsidian was actually erupted during the late Holocene about 2500 years ago, dated by U-Th-Pb, and (U-Th)/He zircon to 2.48 ± 0.47 ka at 2 sigma, and since verified with Ar40/39 dates at 2.83 ± 0.60 ka at 2 sigma as well as IRL recently (Schmitt et al. 2012, 2013, 2019; Wright et al. 2015). This means that this source would not be present in regional archaeological contexts during much of the Archaic, and can stand as a terminal ante quem date archaeologically (see McDonald 1992 at Indian Hill; also Kyle 1996; Hughes and True 1985; Schmitt et al. 2019). Late Archaic Elko-eared dart points were recovered from Indian Hill rockshelter in eastern San Diego County produced from Obsidian Butte, and have also been recovered in San Diego County sites (Hughes and True 1985; Shackley 2017; see Figure 4 here). It appears that not long after eruption, Late Archaic knappers were using Obsidian Butte for tool production (Kyle 1996; Shackley 2017). By the Late Prehistoric period Obsidian Butte became the dominant obsidian used for tool production in San Diego and Imperial Counties of southern California, and to a lesser extent in Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties, as well as far northern Baja California (Hughes and True 1985; Panich et al. 2017; Shackley 2017).

Due to filling of the Salton Basin at least six times during the Holocene creating Lake Cahuilla, Obsidian Butte would be unavailable during the Late Prehistoric period in the region for varying periods of time (Schmitt et al. 2013; Waters 1983; Wright et al. 2015). The filling of Lake Cahuilla and occupation of the lake shore by groups moving west from Arizona was a prime stimulus for the Patayan occupation of what is now San Diego and Imperial Counties, and northern Baja California (Shackley 1981, 1984, 2004). The Kumeyaay, a Yuman speaking group, moved west from their ancestral home in western Arizona first to sites along the Lake Cahuilla shoreline, and finally west to the coast of San Diego County, and northwestern Baja California by about A.D. 1100-1200 (Cooley 1998; Shackley 1981, 1984, 2004; Waters 1982). Obsidian Butte, then, became a part of Kumeyaay geography and territory and the major obsidian toolstone for the group, and likely exchanged with Takic speaking groups to the north in what is now Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties (Cooley 1998; Hughes and True 1985; McGuire and Schiffer 1982; Panich et al. 2017; Shackley 1981, 1984, 1998, 2004; Waters 1982).

Figure 1. Obsidian Butte (Google mapping from 2016)

Figure 2. Detail of obsidian at the East Butte (left), and detail of less vitrophyric boulder at the West Butte (right).

Table 1. Raw elemental concentrations for Obsidian Butte source standards. All measurements in parts per million (ppm). Sample prefixes designate collections from the individual domes as in Figure 1. Sample numbers with prefix "OB" from the early 1980s collection.

| Sample | Locality | Ti | Mn | Fe | Zn | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Ba | Pb | Th |

| 101917-1-1 | East Dome | 1221 | 358 | 15910 | 72 | 138 | 33 | 110 | 332 | 33 | 679 | 11 | 17 |

| 101917-1-2 | East Dome | 1201 | 332 | 15290 | 70 | 133 | 34 | 108 | 327 | 27 | 666 | 12 | 17 |

| 101917-1-3 | East Dome | 1319 | 365 | 17726 | 87 | 142 | 35 | 113 | 338 | 34 | 687 | 10 | 32 |

| 101917-1-4 | East Dome | 1292 | 431 | 17920 | 87 | 143 | 31 | 119 | 356 | 36 | 573 | 12 | 25 |

| 101917-1-5 | East Dome | 1853 | 426 | 17950 | 83 | 140 | 67 | 116 | 334 | 34 | 794 | 12 | 27 |

| 101917-1-7 | East Dome | 1277 | 386 | 17422 | 74 | 141 | 34 | 119 | 353 | 31 | 639 | 14 | 35 |

| 101917-1-9 | East Dome | 1279 | 361 | 17134 | 74 | 133 | 38 | 116 | 344 | 30 | 699 | 12 | 28 |

| 101917-1-10 | East Dome | 1234 | 385 | 17052 | 77 | 137 | 34 | 113 | 340 | 28 | 639 | 15 | 25 |

| 101917-1-11 | East Dome | 1318 | 355 | 15559 | 67 | 125 | 36 | 111 | 335 | 30 | 660 | 14 | 23 |

| 101917-1-12 | East Dome | 1356 | 368 | 16463 | 72 | 133 | 35 | 113 | 332 | 35 | 630 | 12 | 31 |

| 101917-1-13 | East Dome | 1568 | 362 | 16595 | 77 | 134 | 67 | 111 | 344 | 32 | 785 | 17 | 32 |

| 101917-1-14 | East Dome | 1236 | 338 | 16002 | 84 | 158 | 30 | 112 | 342 | 33 | 665 | 9 | 33 |

| 101917-2-1 | Middle Dome | 1455 | 418 | 18126 | 94 | 145 | 39 | 115 | 330 | 28 | 646 | 18 | 21 |

| 101917-2-2 | Middle Dome | 1411 | 388 | 18126 | 84 | 146 | 32 | 119 | 353 | 38 | 677 | 14 | 25 |

| 101917-2-3 | Middle Dome | 1195 | 358 | 15255 | 68 | 126 | 32 | 107 | 323 | 29 | 643 | 8 | 23 |

| 101917-2-4 | Middle Dome | 1359 | 384 | 17892 | 77 | 140 | 43 | 111 | 359 | 32 | 705 | 15 | 24 |

| 101917-2-5 | Middle Dome | 1304 | 399 | 17120 | 73 | 138 | 42 | 110 | 353 | 26 | 721 | 8 | 17 |

| 101917-2-6 | Middle Dome | 1352 | 376 | 16619 | 79 | 136 | 32 | 114 | 345 | 33 | 647 | 11 | 18 |

| 101917-2-7 | Middle Dome | 1327 | 388 | 17528 | 71 | 133 | 39 | 108 | 351 | 33 | 720 | 18 | 21 |

| 101917-3-1 | West Dome | 1424 | 397 | 17985 | 81 | 142 | 33 | 111 | 355 | 29 | 634 | 14 | 31 |

| 101917-3-2 | West Dome | 1563 | 447 | 20466 | 93 | 156 | 33 | 132 | 357 | 30 | 661 | 16 | 28 |

| 101917-3-3 | West Dome | 1248 | 348 | 16975 | 68 | 137 | 31 | 109 | 335 | 25 | 590 | 7 | 23 |

| 101917-3-4 | West Dome | 1273 | 386 | 15833 | 72 | 152 | 35 | 104 | 327 | 23 | 659 | 14 | 27 |

| 101917-3-5 | West Dome | 1317 | 368 | 15854 | 79 | 122 | 26 | 112 | 308 | 33 | 641 | 15 | 24 |

| 101917-3-6 | West Dome | 1438 | 399 | 17954 | 90 | 149 | 36 | 119 | 334 | 35 | 691 | 19 | 24 |

| 101917-3-7 | West Dome | 1338 | 379 | 18626 | 84 | 152 | 37 | 117 | 344 | 30 | 701 | 12 | 26 |

| 101917-3-8 | West Dome | 1477 | 388 | 19171 | 81 | 144 | 37 | 116 | 353 | 36 | 670 | 15 | 29 |

| 101917-3-9 | West Dome | 1223 | 376 | 16260 | 75 | 129 | 32 | 113 | 313 | 31 | 639 | 11 | 21 |

| 101917-3-10 | West Dome | 1410 | 414 | 18974 | 96 | 152 | 30 | 129 | 341 | 32 | 629 | 14 | 41 |

| 101917-3-11 | West Dome | 1538 | 440 | 19505 | 86 | 139 | 38 | 116 | 361 | 31 | 728 | 13 | 27 |

| OB-1 (1980s) | East Dome | 1183 | 403 | 17247 | 78 | 134 | 26 | 116 | 331 | 31 | 641 | 18 | 23 |

| OB-2 | East Dome | 1664 | 438 | 21732 | 76 | 125 | 53 | 98 | 422 | 30 | 727 | 24 | 18 |

| OB-3 | East Dome | 1640 | 449 | 21495 | 76 | 132 | 52 | 100 | 435 | 27 | 767 | 19 | 18 |

| OB-4 | East Dome | 1435 | 410 | 19807 | 78 | 137 | 28 | 125 | 369 | 35 | 594 | 19 | 20 |

| OB-5 | East Dome | 1366 | 406 | 18883 | 73 | 126 | 45 | 105 | 377 | 26 | 702 | 20 | 17 |

| OB-6 | East Dome | 964 | 365 | 14559 | 72 | 131 | 20 | 119 | 303 | 33 | 552 | 20 | 26 |

| OB-7 | East Dome | 1464 | 424 | 19694 | 71 | 122 | 46 | 94 | 419 | 22 | 730 | 18 | 20 |

| OB-8 | East Dome | 969 | 381 | 16358 | 80 | 148 | 20 | 133 | 313 | 35 | 625 | 21 | 20 |

| OB-9 | East Dome | 1598 | 422 | 19922 | 75 | 121 | 47 | 98 | 415 | 24 | 684 | 19 | 15 |

| OB-10 | East Dome | 1467 | 401 | 19067 | 68 | 121 | 48 | 94 | 405 | 21 | 701 | 19 | 23 |

| OB-11 | East Dome | 1358 | 387 | 17890 | 75 | 133 | 41 | 113 | 355 | 29 | 685 | 19 | 24 |

| OB-12 | East Dome | 1758 | 462 | 22674 | 81 | 129 | 51 | 100 | 437 | 27 | 804 | 17 | 24 |

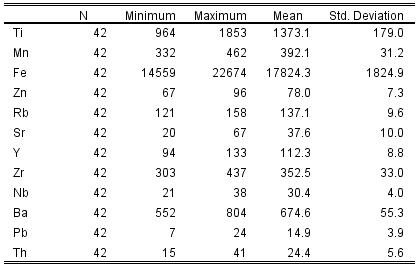

Table 2. Mean and central tendency for the Obsidian Butte data shown in the Table 1.

Table 3. Selected major and minor oxides for sample Obsidian Butte-9 (OB-9, East Butte)

|

Sample |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

CaO |

Fe2O3 |

K2O |

MgO |

MnO |

Na2O |

TiO2 |

|

Obsidian Butte, CA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

OB-9 |

73.85 |

12.49 |

1.16 |

2.95 |

4.36 |

<.001 |

0.07 |

4.40 |

0.24 |

|

RGM-1 |

75.68 |

12.48 |

1.30 |

1.81 |

4.55 |

<.001 |

0.04 |

3.8 |

0.19 |

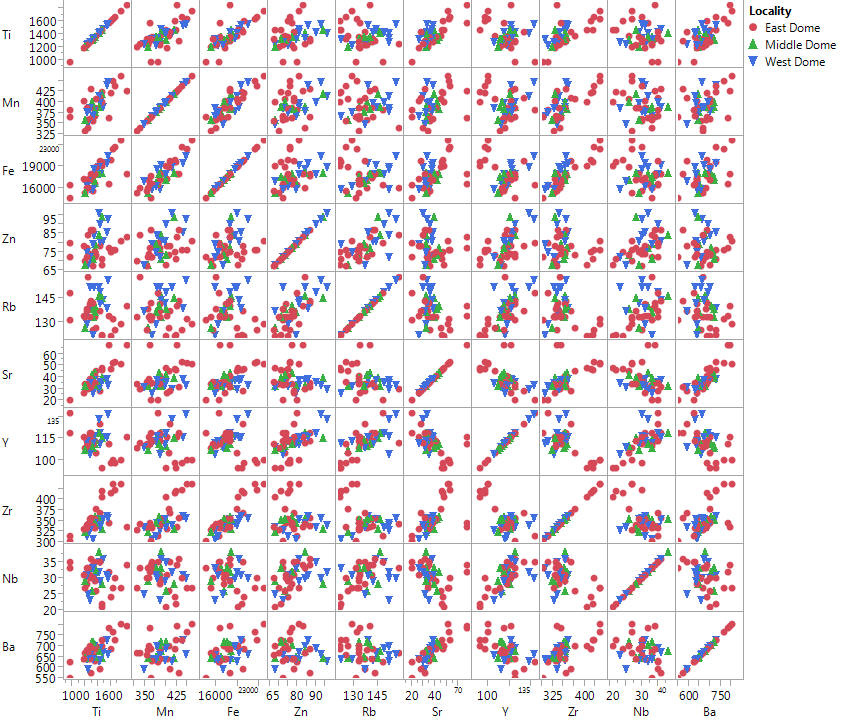

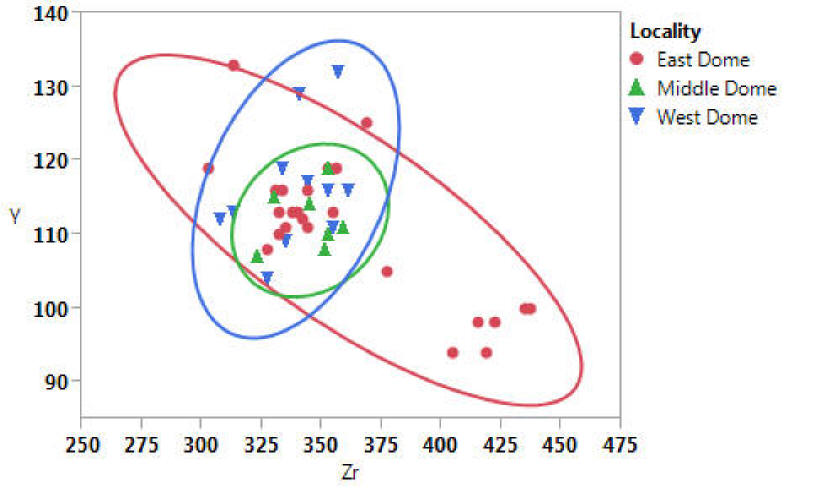

Figure 2. Matrix plot of 10 elements from the Obsidian Butte analysis above.

Figure 3. Bivariate plot of four elements from the three buttes. Note that as evident in the matrix plot that the East Dome is the most variable, but all the locality's elemental concentrations overlap at 95% confidence (see analysis in Hughes 1986).

Figure 4. Late Archaic and Late Prehistoric projectile points produced from Obsidian Butte obsidian. Left image: Late Archaic Elko-Eared dart point from Jacumba Valley, southeastern San Diego County (bottom; no site number), and Late Prehistoric Desert Side-Notched points from the Scissors Crossing site (CA-SDI-857) northeastern San Diego County, from Shackley (2017) top; right image: Desert Side-Notched points from Arrowmakers Ridge (CA-SDI-913, Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, in the Peninsular Ranges, east San Diego County, California (Shackley 2000; see also True 1970).

References

Cooley, T.G. (1998) Observations on settlement and subsistence during the Late La Jolla Complex: preceramic interface as evidenced at site CA-SDI-11,787, lower San Diego River Valley, San Diego County, California. Proceedings of the Society for California Archaeology 11:1-6.

Ericson, J.E. (1977) Prehistoric exchange systems in California: the results of obsidian dating and tracing. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Heizer, R.F. and A.E. Treganza (1944) Mines and Quarries of the Indians of California. California Division of Mines Bulletin 40:291-359.

Hughes, R.E. (1986). Trace element composition of Obsidian Butte, Imperial County, California. Southern California Academy of Science Bulletin 85:35-45.

Hughes, R.E., and D.L. True (1985) Perspectives on the distribution of obsidians in San Diego County, California. North American Archaeologist 6:325-339.

Kyle, C. E. (1996) A 2,000 year old milling tool kit from CA-SDI-10148, San Diego, California. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 32:76–87.

McDonald, A.M. (1992) Indian Hill Rockshelter and Aboriginal Cultural Adaptation in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, Southeastern California. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Riverside.

Panich, L.M., M.S. Shackley, and A. Porcayo Michelini (2017) A reassessment of archaeological obsidian from southern Alta California, and northern Baja California. California Archaeology 9:53-77.

Robinson, P.T., W.A. Elders, and L.J.P. Muffler (1976) Quaternary volcanism in the Salton Sea geothermal field, Imperial Valley, California. Geological Society of America Bulletin 87:347-360.

Schmitt, A. K., A. Martin, D. F. Stockli, K. A. Farley, and O. M. Lovera (2012), (U-Th)/He zircon and archaeological ages for a late prehistoric eruption in the Salton Trough (California, USA), Geology 41:7–10

Schmitt, A.K., A. Martin, B. Weber, DF. Stockli, H. Zou, and C. Shen (2013) Oceanic magmatism in sedimentary basins of the northern Gulf of California rift. GSA Bulletin 125:1833-1850.

Schmitt, A.K., A.R. Perrine, E.J. Rhodes, and C. Fischer (2019) Age of Obsidian Butte in Imperial County, California, through infrared stimulated luminescence dating of potassium feldspar from tuffaceous sediment. California Archaeology 11:5-20.

Shackley, M.S. (1981) Late Prehistoric Exchange Network Analysis in Carrizo Gorge and the Far Southwest. Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, San Diego State University.

Shackley, M.S. (1984) Archaeological Investigations in the Western Colorado Desert: A Socioecological Approach (3 volumes). Volume 1 published by Coyote Press, Salinas, California.

Shackley, M.S., (1998) Patayan Culture Area. In Archaeology of Prehistoric North America: An Encyclopedia, edited by G. Gibbon, pp. 629-632. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

Shackley, M.S. (2000) Late prehistoric obsidian projectile point source provenance and technology from three late prehistoric contexts in San Diego County, California: The Rose Canyon Site, Arrowmaker’s Ridge, and W-256 (Ramona). Report prepared for the San Diego Museum of Man, San Diego, California.

Shackley, M.S., Ed. (2004) The Early Ethnography of the Kumeyaay, with reprints by T.T. Waterman, L. Spier, and E.W. Gifford. Classics in California Anthropology, Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology, University of California Press, Berkeley.

Shackley, M.S. (2017) The Shackley San Diego County archaeological collection. Manuscript submitted to the Southern California Information Center, San Diego State University.

Shackley, M.S. (2019) Natural and Cultural History of the Obsidian Butte source, Imperial County, California. California Archaeology 11:21-44.

Treganza, A.E. (1942) An archaeological reconnaissance of northeastern Baja California and southeastern California. American Antiquity 8:152-13.

True, D.L. (1970) Investigation of a Late Prehistoric Complex in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, San Diego County, California. Archaeological Survey Monograph, Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Waters, M.R. (1982) The Lowland Patayan ceramic tradition. In R.H. McGuire, and M.B. Schiffer, Eds. Hohokam and Patayan: Prehistory of Southwestern Arizona, pp 275-299. New York: Academic Press.

Waters, M. R (1983) Late Holocene lacustrine chronology and archaeology of ancient Lake Cahuilla, California. Quaternary Research 19: 373-387.

Wright, H.M., J.A. Vasquez, D.E. Champion, A. T Calvert, M.T. Mangan, M. Stelten, K.M. Cooper, C. Herzig, and A. Schreiner, Jr. (2015) Episodic Holocene eruption of the Salton Buttes rhyolites, California from paleomagnetic, U-Th, and Ar/Ar dating. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 16:1198-1210.

![]()

This page maintained by Steve Shackley (shackley@berkeley.edu).

Revised: 07 July 2024

![]() Back to

the SW obsidian source page

Back to

the SW obsidian source page

![]()