SOURCES OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL OBSIDIAN IN THE NORTH AMERICAN SOUTHWEST

Albuquerque, New Mexico

“Whenever you have small samples, you run a very real risk of mischaracterization.” (Tim White, 2015)

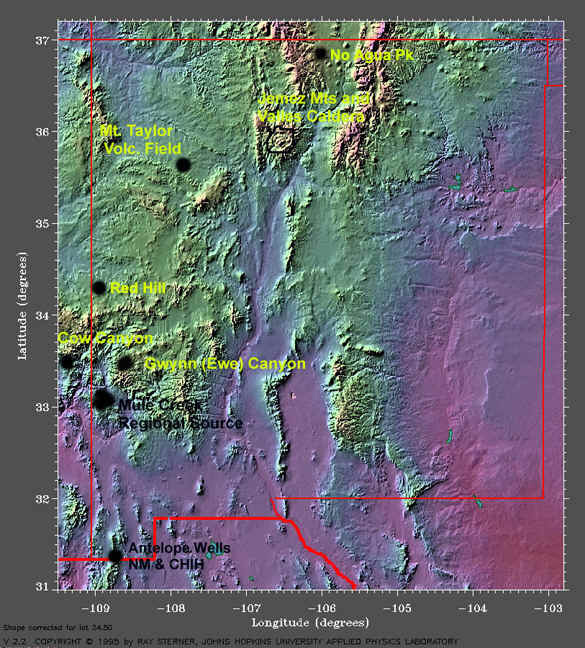

![]()

This is an image map with hotspots linked to descriptions and images of the sources. Just click on the source location.

If you can't view or use this image, or prefer to use a list, just scroll past the image.

![]()

Note: references cited are from Shackley (1990, 1995, 2005)

What Obsidian Sources Hath Wrought in Southwestern Archaeology. Archaeology Cafe lecture, 2011

![]() To a technical definition of obsidian, particularly for the Southwest

To a technical definition of obsidian, particularly for the Southwest

![]() A word about the silicic volcanic history of the Southwest

A word about the silicic volcanic history of the Southwest

![]()

![]() To

Steve Reynolds (ASU) 3D Arizona Geology Maps

To

Steve Reynolds (ASU) 3D Arizona Geology Maps

The obsidian sources within this field are, perhaps, the best studied in the Southwest (Jack 1971; Robinson 1913; Sanders et al. 1982; Schreiber and Breed 1971; Shackley 1988). Although the chemical variability within sources in this field is generally less than in the mid-Tertiary sources to the south, the magmatic relationships between some of these sources as previously reported are probably in error (Jack 1971; Sanders et al. 1982).

![]() Slate Mountain (Wallace Tank).

Slate Mountain (Wallace Tank).

![]() San Francisco Peaks (Fremont-Agassiz Saddle).

San Francisco Peaks (Fremont-Agassiz Saddle).

![]() Partridge Creek (Round Mountain).

Partridge Creek (Round Mountain).

These marekanite sources are some of the finest quality obsidians in the Southwest. Unfortunately, they generally produce the smallest 'maximum size' nodules. Nodules are rarely greater than 10 cm in diameter, but the glass is invariably free of phenocrysts and very vitreous. Experiments with these small nodules, and the material recorded on these sources indicates that bipolar reduction was the most common reduction method used on the small obsidian cores. Some flakes can be successfully removed in freehand percussion when the core size is over four centimeters and there is an adequate platform.

These obsidians also exhibit extreme variability in color and opacity even within a given source. While it is usually possible to distinguish some of the northern Arizona glasses megascopically, it is essentially impossible with the marekanite sources. For example, Superior (Picketpost Mtn) and Topaz Basin are usually nearly transparent in thin flakes, but some specimens have dark bands (bubbles or crystallites) that look very similar to Cow Canyon, Red Hill, Sauceda, or Vulture.

![]() Vulture

(new expanded data and description - October 2008)

Vulture

(new expanded data and description - October 2008)

![]() Superior

(Picketpost Mountain)

Superior

(Picketpost Mountain)

Three of the major sources in western New Mexico, Antelope Wells, Mule Creek, and Red Hill have all been reported by Findlow and Bolognese (1980, 1982), and quantitatively analyzed by Hughes (1988a). The information offered here is additional updated material gathered before Hughes (1988a) study.

Red Hill source material does not often appear in archaeological context in central and southern Arizona probably due to intervening sources in eastern and central Arizona (Shackley 1986a). Antelope Wells material does appear in Archaic and Hohokam sites throughout central Arizona probably since it is the only source in the southeastern Arizona/southwestern New Mexico region.

The sources in western and southwestern New Mexico and eastern Arizona are part of the Mogollon-Datil Volcanic Province and have magmatic affinity through the extensive late Tertiary silicic volcanism in western New Mexico and re-melting the granite basement (Elston et al. 1976; Shackley et al. 2017). All these sources are associated with the large Tertiary ash flows and lavas (Tur and Tdrn) in the region (see Weber and Willard 1959; Willard and Weber 1958). The relatively similar trace chemistry of these three sources are the result of common magmatic origin. Elston et al. (1976) suggest that most of this material was emplaced between 43 and 21 million years ago concentrated in an area extending from the San Augustine Plains to about 150 km south (the Mogollon-Datil Province) including the Antelope Wells source. They divide the rocks into two suites: a calc-alkaline suite (CAS; dating from 43 to 29 m.y.b.p.) and a high silica rhyolite suite (HSR; dating from 32 to 21 m.y.b.p), the latter the eruptive dates of the Mogollon-Datil obsidian. The marekanites in these sources are further examples of the Tertiary age remnants that have been resistant to hydration. In this case, the silica rich contents and low water content probably saved them from rapid hydration.

[updated in Shackley 1995] One of the more striking developments in obsidian studies in this area of the Southwest is related to the problem of understanding the secondary deposition of obsidian from some of the large Tertiary sources, and the discovery of significant geochemical variability in what was originally known as the Mule Creek source (Shackley et al. 2016). In the first case, Mule Creek and Cow Canyon marekanites were found to be eroding into the San Francisco and Gila Rivers at least 50 km and possibly 100 km from the primary sources. The Cow Canyon and Mule Creek marekanites are mixed in the Gila River alluvium near Safford, Arizona in an approximate 3/1 ratio (Shackley 1992a). In this region where in the Classic Period, Hohokam, Salado, and Mogollon "boundaries" abut, this can cause considerable problems in dealing with issues of exchange and interaction when only the primary deposits are considered to be the "source." (see Mills et al. 2013).

![]() Mount

Taylor Volcanic Field (Grants Ridge/Horace Mesa) updated September 2013

Mount

Taylor Volcanic Field (Grants Ridge/Horace Mesa) updated September 2013

Rabbit Mtn and Cerro Toledo Rhyolite

Valles Rhyolite (Cerro del Medio)

Canovas Canyon Rhyolite (Bear Springs Peak)

Bearhead Rhyolite (Paliza Canyon)

![]() The

Taos Plateau Volcanic Field and No Agua Peak Obsidian

The

Taos Plateau Volcanic Field and No Agua Peak Obsidian

A number of new and re-investigated sources of archaeological obsidian are currently being examined in a continuing project between the University of California, Berkeley, and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH)/FONDO Nacional Arquelógico of Mexico (Shackley 1993b, 1994b). By agreement with INAH, these sources will be reported separately in detail. Other than the San Felipe Tertiary source in the far northern part of the peninsula, and Los Vidrios in northern Sonora these sources rarely appear in archeological contexts north of the border. Additionally, obsidian research in the neighboring Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora still is rudimentary, but work is progressing. Recent analyses of artifact obsidian from sites along the eastern edge of the Sierra Madre in Chihuahua in the Hearst Museum collections, and an extensive analysis of Archaic period cruciforms from Texas and Chihuahua indicates at least five as yet unlocated sources in the region besides the Antelope Wells source in the northern part of this state and New Mexico. This study will be reported elsewhere as the work matures (see Shackley et al. 1996).

Geology of Northwest Mexico: A Brief Synopsis

BAJA CALIFORNIA

![]() Valle

del Azufre, Baja California Sur

Valle

del Azufre, Baja California Sur

SONORA

CHIHUAHUA

![]() Lago

Barreal, East-Central Chihuahua

Lago

Barreal, East-Central Chihuahua

![]() Sierra la

Breña, Northwest Chihuahua

Sierra la

Breña, Northwest Chihuahua

![]() Sierra

Fresnal, North-Central Chihuahua

Sierra

Fresnal, North-Central Chihuahua

This region was not covered in the earlier study, but these sources on the periphery of the Southwest merit some attention. The two sources reported here have been discussed in detail in Shackley (1994c). Obsidian Butte glass has been analyzed quantitatively by Ericson (1977) and Hughes (1986) elsewhere and will not be reported here. My analyses of Obsidian Butte source standards and archaeological obsidian from the region are comparable (i.e. Shackley 1993c).

![]() Bristol Mountains

(Bagdad), California

Bristol Mountains

(Bagdad), California

![]() Devil Peak, Clark

County, Nevada

Devil Peak, Clark

County, Nevada

![]() Obsidian Butte,

Imperial County, California

Obsidian Butte,

Imperial County, California

![]()

This page maintained by Steve Shackley .

Copyright © 2020 M. Steven Shackley. All rights reserved.Revised:Friday, 17 January 2025 08:31 -0700

These data are based on work partly or wholly supported by the National Science Foundation under Grants DBS-9205506, BCS 0001395, BCS 071633, and BCS-0810448 to M. Steven Shackley. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

All materials appearing on this Web (http://www.swxrflab.net/) may not be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system without prior written permission of the publisher, except for educational purposes, and in no case for profit.

![]()