LOS SITIOS

DEL AGUA, NORTHERN SONORA

The vent and dome at Los Sitios del Agua

Based on a 1992 analysis of 71 obsidian

artifacts from various sites located in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,

Steve Shackley noted 10 artifacts that exhibited an elemental chemistry

different from any yet identified in the Southwest (Shackley 1992, 2005).

Since then, this unlocated source called AZ Unknown A, has been found in

archaeological sites of various age throughout southern Arizona, as far

north as the Phoenix Basin (Shackley 2005; Shackley and Tucker 2001).

While exploring Historic era trails in northwestern Sonora, Mexico, members

of the Ajo Chapter of the Arizona Archaeological Society discovered a

previously unknown source of obsidian and other archaeological sites

adjacent to the Rio Sonoyta in northern Sonora (Figure 1). This newly

discovered source, called Los Sitios del Agua, is AZ Unknown A and finally

locates this most vexing unknown obsidian sources in the region and provides

important source provenance data for the Archaic through Historic periods in

the southern Southwest.

THE DISCOVERY

During

the spring of 2006, several members of the Ajo Chapter of the Arizona

Archaeological Society were exploring back roads in northwestern Sonora,

Mexico. After emerging onto a wide flat terrace immediately above the

floodplain of the Rio Sonoyta, nodules of obsidian were observed among the

gravels covering the terrace. During a return visit in the fall of 2006, an

obsidian quarry was discovered in the hills at the northern edge of this

same terrace. Based on the results of a trace element analysis of two

samples conducted by the Northwest Research Obsidian Studies Laboratory in

Corvallis, Oregon it is known that the characteristics of this obsidian

(Table 1) are the same as those from Los Vidrios Obsidian Quarry (LV)

(Skinner 2007a) as originally reported by Shackley (1988, 1995, 2005).

In the spring

of 2007, exploration along the banks of the Rio Sonoyta approximately 8-9 km

downstream from the LV quarry revealed obsidian marekanites littering the

sides of a rhyolite dome complex. The trace element characteristics of four

samples of this obsidian (Table 1) did not match those from LV, but instead

were the same as those classified as “Unknown 1" by Skinner (2007a, 2007c)

and as AZ Unknown A discovered by Shackley (1992, 1995, 2005). The obsidian

source for these samples previously known as Unknown 1 and AZ Unknown A has

now been located and will be named the Los Sitios del Agua Obsidian Quarry (LSA).

In October 2008 Rick and Sandy Martynec and Steve Shackley re-visited the

rhyolite dome complex for two days, recorded and mapped the LSA source

again, and collected over 300 marekanite samples for study at Berkeley.

While it is

considered part of the same volcanic field as Los Vidrios, the composition,

that of a mildly peralkaline rhyolite, is quite different (Vidal-Solano et

al. 2008; see

http://swxrflab.net/los_sitios_del_agua.htm). The rhyolite dome is also

called Vidrios Viejos and as mentioned above has an 40Ar/39Ar

date of 14.27±0.15 Ma statistically similar to Los Vidrios (Vidal-Solano

et al. 2008:697.

THE

OBSIDIAN AT LOS SITIOS DEL AGUA

Los Sitios del

Agua is a probable Tertiary Period dome complex oriented in a

northwest-southeast arc (see Fig. 2). Typical of Tertiary rhyolite dome

complexes that produce obsidian, Los Sitios del Agua exhibits perlitic lava

bodies with abundant remnant marekanites, some as large as seven to eight

centimeters, and many near five centimeters (Shackley 2005; Fig. 3 here).

As with Los

Vidrios, the Los Sitios del Agua domes appear to be part of a bimodal

volcanic field known as the Sierra Pinacate Volcanic Field that consists of

initial Tertiary events, mainly rhyolite in composition followed by mainly

mafic eruptive events to the west of the earlier rhyolite during the

Quaternary including 10 maar volcanic events (Donnelly 1974; Gutmann 2007;

Gutmann et al. 2000). Virtually no geological research has been

directed toward the rhyolite on the eastern portion of the volcanic field

other than the initial work by Shackley (1988, 1995, 2005).

The Los Vidrios dome complex west of Los Sitios del Agua

The majority

of obsidian at the LSA quarry does not appear to have been formed in the

same manner as that at Los Vidrios. Virtually all of the LSA marekanites are

remnant marekanites in perlitic lava. None of the marekanites were

produced by ash flows as in the Los Vidrios case (Shackley 1988; Figure 3

here). In addition to the angular quality of the obsidian from the LSA

quarry, there are color variations within the site. Scattered about and

localized in at least one area are light grey marekanites of obsidian.

Even more startling is a small quarry near the center of the LSA quarry

where beautiful, jade green colored obsidian was apparently mined based on

what appears to be a small prospect; this green obsidian has been termed

Kate’s Green after its discoverer. When tested by Skinner (2007c) this

green obsidian was found to have nearly the same trace element composition

as the surrounding jet black obsidian. Analysis of source standards

here in the Berkeley lab indicates substantive differences in barium in the

green samples, however (Tables 2 and 3). The other measured elements

are similar (Table 3). It is obvious that this unique colored obsidian

held a special appeal. It still does today.

The other measured

elements are similar. It is obvious that this unique colored obsidian held

a special appeal. It still does today. The composition as reported by

Vidal-Solano et al. using plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy matches well

with the EDXRF data from this lab (2008:695).

SOURCE DESCRIPTION

Although most of the surface obsidian at the LSA quarry exhibits a shiny,

almost freshly broken appearance, only a few lithic reduction stations were

noted. While examination of the site revealed scattered reduction flakes and

cores, there are a few locations where numerous nodules have been tested by

the bipolar reduction method. Here amongst the layers of debitage can

be found large, thin primary flakes, some are quite long exceeding 5 cm in

length. This undoubtedly was a characteristic desired for the production of

the small, delicately made projectile points and cutting and scraping tools

found on nearby sites. One is led to conclude from the lack of secondary and

final pressure flaking debitage at the LSA quarry, that the larger and more

desirable flakes were transported to other locations for further and final

refinement. Knapping experiments by Shackley noted that LSA obsidian is

considerably less brittle than the nearby Los Vidrios obsidian that occurs

in much larger quantities. Production of a Desert Side-notched

projectile point from the production of a bipolar flake took less than 20

minutes with excellent predictability. As discussed below, this may be

why Los Sitios del Agua is common in archaeological contexts to the north

even though the source material is numerically inferior to Los Vidrios.

Physically, the obsidian at the LSA quarry encompasses an area that measures

approximately 800 meters north-south by 850 meters east-west; the base of

the small hills are at 207 meters above sea level and rise to an elevation

of 224 meters above sea level. The density of obsidian on the ground surface

varies widely within the quarry from areas where there are no nodules to

others where there are more than 500 in one square meter. There

appears to be virtually no secondary deposition into the Rio Sonoyta, at

least as evident today. This may be why it was not discovered by the

earlier study in the 1980s (Shackley 1988).

The high surface density of marekanites

at Los Sitios del Agua

XRF ANALYSIS

Of over 300 marekanite

samples collected from Los Sitios del Agua, 40 samples (»

13%) were analyzed by energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence spectrometry for

16 elements, ten of which are reported here (Tables 2 and 3). The

laboratory and instrument protocol is here (see also

Shackley et al. 2016).

Immediately apparent is that

this rhyolite lava is a mildly peralkaline rock. These volcanic rocks are

generally seen as a division of volcanics where the proportion of alumina

(AlO2) is less than that of sodium and potassium oxides combined,

but more importantly generally exhibits relatively high iron and zirconium

values (Best 1982; Cann 1983; Hildreth 1981; Shackley 2005; see Figure 4

here). These peralkaline volcanic rocks, including rhyolitic obsidian is

common in rift regions were more mafic lava associated with the mantle is

sampled and crustal volcanism occurs, such as the Great Rift Valley in

eastern Africa. In the Rio Sonoyta case, the elemental composition of Los

Vidrios and Los Sitios del Agua couldn’t be more different (Figure 4).

There are no peralkaline obsidians north of the International border, but

are quite common associated with the Sierra Madre Occidental, probably the

largest rhyolite field in the world, and the Chihuahuan Basin and Range

just to the east of the Sierra of eastern Sonora and Chihuahua. (Gunderson

et. al. 1986; Fralick et al. 1998; Shackley 2005). In obsidian, peralkaline

chemistry is objectified by very dark often opaque glass, and glass that is

often green when viewed with transmitted light both caused by a high iron

content. The most archaeologically famous peralkaline glass in the New

World is that from Sierra de Pachuca, in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico

(Barker et al. 2002; Tenoria 1998). The obsidian from Los Sitios del Agua

Areas A, B, C, and E, are all translucent dark green similar to Pachuca,

while the marekanites from Area D is an opaque light green - all due to the

relatively high iron. This makes Los Sitios del Agua obsidian the most

megascopically distinct of the Sonoran Desert obsidian sources.

LOS SITIOS DEL AGUA IN SITES NORTH OF THE BORDER

Besides the

ten artifacts analyzed by Shackley from Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

just north of the border, obsidian from Los Sitios del Agua has also been

recorded (as AZ Unknown A) in other sites as far north as the Phoenix

Basin. Table 4 exhibits the number of artifacts produced from Los Sitios

del Agua in Arizona sites. The vast majority of Los Sitios del Agua

obsidian is from sites in southern Arizona, including sites in the Phoenix

Basin. It is almost always in assemblages where Los Vidrios obsidian also

occurs, suggesting that marekanites from both sources were collected

prehistorically together while traveling along the Rio Sonoyta as discussed

above. It was not found at the Preclassic site of Snaketown on the Gila

River Indian Nation, but a few were recovered from surface sites on the Gila

River Indian Nation (Shackley 2005; Table 4 here). It also was not

recovered from the Classic Period sites of Pueblo Grande or Casa Grande (Bayman

and Shackley 1999; Peterson et al. 1997).

CONCLUSION

The discovery of the Los

Sitios del Agua obsidian source in northern Sonora solves one of the unlocated sources in the Southwest. The glass proper, a green peralkaline

obsidian, is unique in the Sonoran Desert for its color and just as unique

chemically, and probably held value in prehistory. Los Sitios del Agua is a

small dome complex covering a much smaller area than the extensive dome

complex of Los Vidrios, mostly across the Rio Sonoyta. It does, however,

occur in sites at least as far north as the Phoenix Basin and often in

association with artifacts produced from Los Vidrios obsidian. While these

two Sonoyta River Valley obsidian sources were likely sampled by groups

moving north or south through the area, it is not necessarily clear whether

they can be used as a signature of shell exchange during any particular time

period. Reconnaissance of the valley by members of the Arizona

Archaeological Society suggests that all time periods, particularly

Preclassic through Historic periods are represented at sites in the region.

To References

Table 1. Results of previous XRF Studies modified to include new

findings (mean values)

|

|

|

Trace Element Concentrations1 |

Ratios |

|

|

Quarry Site |

Zn |

Pb |

Rb |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Nb |

Ti |

Mn |

Ba |

Fe2O3 |

Fe:Mn |

Fe:Ti |

|

Los Vidrios (Skinner 2007a) |

82 |

28 |

258 |

14 |

67 |

216 |

28 |

445 |

178 |

16 |

1.29 |

62.8 |

93.9 |

|

Los

Vidrios (Shackley 1995) |

n.r.2 |

n.r. |

260 |

14 |

75 |

235 |

32 |

784 |

208 |

82 |

1.31 |

n.r |

n.r. |

|

Unknown 1 (Skinner 2007a)

Los Sitios del Agua (LSA) |

113 |

25 |

140 |

15 |

83 |

691 |

47 |

1092 |

444 |

33 |

3.24 |

60.1 |

97.0 |

|

AZ

Unknown A (Shackley 1992, 1995, 2005) |

n.r. |

n.r |

141 |

18 |

79 |

713 |

47 |

2265 |

566 |

n.r |

n.r |

n.r |

n.r |

1

All trace element values reported in parts per million |

|

2

n.r. = no report |

|

|

To the raw elemental data

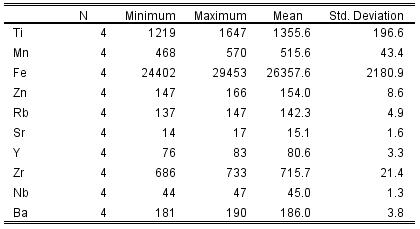

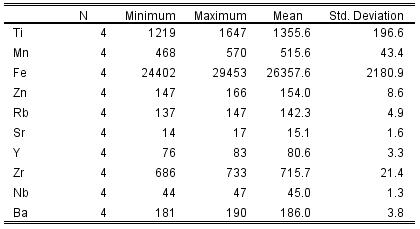

Table 2. Mean and central

tendency for elemental concentrations for the Los Sitios del Agua source

standards for Localities A, B, C, and E source standards analyzed at Berkeley.

All measurements in parts per million (ppm).

|

|

Ti |

Mn |

Fe |

Zn |

Rb |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Nb |

Ba |

|

N |

|

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

36 |

34 |

|

Mean |

1261 |

543 |

25821 |

148 |

143 |

12 |

81 |

724 |

48 |

121 |

|

Std.

Error of Mean |

16 |

38 |

335 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|

Std.

Deviation |

94 |

230 |

2008 |

11 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

20 |

3 |

13 |

|

Minimum |

1052 |

384 |

20158 |

127 |

126 |

10 |

72 |

666 |

40 |

93 |

|

Maximum |

1455 |

1727 |

29443 |

170 |

156 |

17 |

88 |

762 |

56 |

142 |

Table 3. Mean

and central tendency for Los Sitios del Agua for Locality D (green marekanites)

source standards analyzed at Berkeley (note barium values versus data in Table

2). All measurements in parts per million (ppm).

Table 4. Number

of artifacts produced from Los Sitios del Agua in various sites in Arizona

analyzed at Berkeley as of 2008.

|

|

|

Site or

Project |

Number

of LSA samples |

Reference |

|

Organ

Pipe Cactus Nat. Monument |

10 |

Shackley 1992 |

|

Gila

River Indian Nation (surface survey) |

4 |

Shackley 2004, 2006 |

|

Tumacacori Nat. Hist. Park |

2 |

Shackley 2008a |

|

Ajo

Sites (BLM) |

5 |

Shackley 2008b |

|

Cabeza

Prieta Nat. Wildlife Refuge |

10 |

Shackley 2008c |

|

Tohono

O'odahm Nation |

2 |

Shackley 2008d |

|

|

|

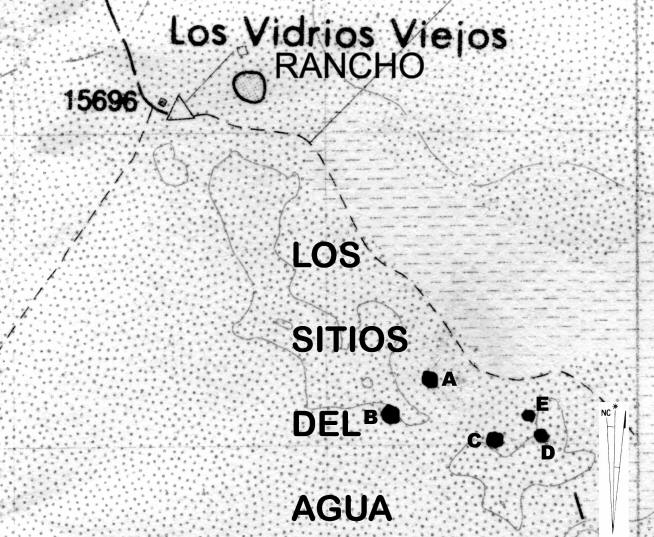

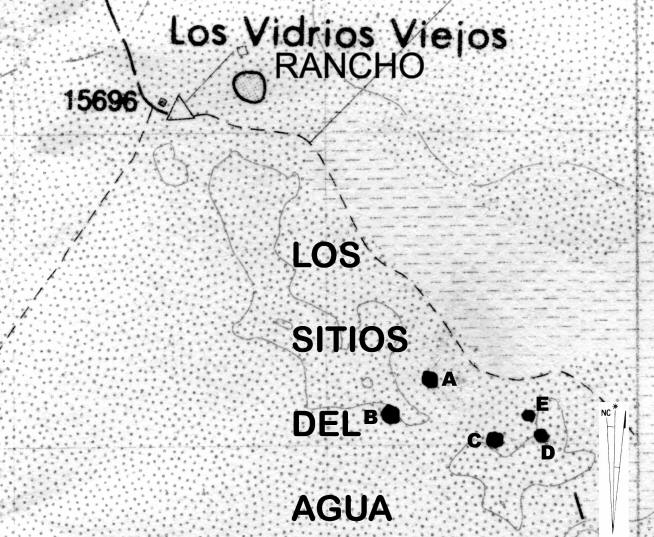

Figure 2. The

Los Sitios del Agua dome complex and surrounding features. Letters denote

collection areas recorded, analyzed, and discussed in text (see Table 1).

Rancho Los Vidrios Viejos is that structure mentioned in Shackley (1988) from

the 1985 survey. Marker 15696 is the INEGI, Mexico federal marker. Grid is

1000 meters, declination is 13º 15' in 1981, adapted from the El Papalote

(H12A13) Sonora/Arizona sheet, INEGI, Mexico.

Figure 3.

Marekanite remnants in perlitic lava at Area B, Los Sitios del Agua.

Figure 4. Rb

versus Zr biplot of source standards from Los Sitios del Agua and Los Vidrios,

Sonora. Measurements in parts per million (ppm).

Figure 5. Zr

versus Rb, and Ba versus Zr of the Los Sitios del Agua source standards.

Note the higher Ba in Area D samples. The other sample areas are very

similar in the other two elements selected.

References

Barker, A.W., C.E. Skinner, M.S. Shackley, M.D. Glascock, and

J.D. Rogers

2002 Mesoamerican Origin

for an Obsidian Scraper from the Precolumbian Southeastern United States.

American Antiquity 67:103-108.

Bayman, J. M. and M. S. Shackley

1999 Dynamics of Hohokam

Obsidian Circulation in the North American Southwest. Antiquity

73:836-845.

Best, M.G.

1982 Igneous and

Metamorphic Petrology. W.H. Freeman, New York.

Cann, J.R.

1983 Petrology of Obsidian Artefacts. In

The Petrology of Archaeological Artefacts, edited by D.R.C. Kempe and A.P.

Harvey, pp. 227-255. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Davis, M.K., T.L. Jackson, M.S.

Shackley, T. Teague, and J. Hampel

1998 Factors Affecting the Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence (EDXRF)

Analysis of Archaeological Obsidian. In Archaeological Obsidian Studies:

Method and Theory, edited by M.S. Shackley, pp. 159-180. Springer/Plenum

Press, New York.

Fralick, P.W.,

J.D. Stewart, and A.C. MacWilliams

1998 Geochemistry of

West-Central Chihuahua Obsidian Nodules and Implications for the Derivation of

Obsidian Artefacts. Journal of Archaeological Science 25:1023-1038.

Gunderson, R., K. Cameron,

and M. Cameron

1986 Cenozoic High-K

Calc-Alkalic and Alkalic Volcanism in Eastern Chihuahua, Mexico: Geology and

Geochemistry of the Benevides-Pozos Area. Geological Society of America

Bulletin 97:737-753.

Hildreth, W.

1981 Gradients in Silicic

Magma Chambers: Implications for Lithospheric Magmatism. Journal of

Geophysical Research 86:10153-10192.

Peterson, J., D.R. Mitchell,

and M.S. Shackley

1997 The Social and

Economic Contexts of Lithic Procurement: Obsidian from Classic Period Hohokam

Sites. American Antiquity 62:231-259.

Shackley, M. Steven

1988 Sources of

Archaeological Obsidian in the Southwest: An Archaeological, Petrological, and

Geochemical Study. American Antiquity 53:752-772.

1990 Early Hunter-Gatherer Procurement Ranges in the Southwest: Evidence

from Obsidian Geochemistry and Lithic Technology. Ph.D. dissertation,

Arizona State University, Tempe.

1992 An Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence

(EDXRF) Analysis of 71 Obsidian Artifacts from Organ Pipe Cactus National

Monument, Southern Arizona. Ms. on file with the National Park Service,

Western Archaeological and Conservation Center, Tucson.

1995 Sources of

Archaeological Obsidian in the Greater American Southwest: An Update and

Quantitative Analysis. American Antiquity 60(3):531-551.

2004 Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from Various Contexts on the

Gila River Indian Community Land, Central Arizona. Report Prepared for the Gila

River Indian Nation.

2005 Obsidian: Geology and Archaeology in the North American Southwest.

University of Arizona Press. Tucson.

2006 Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from Various Contexts on the

Gila River Indian Community Land, Central Arizona II. Report Prepared for the

Gila River Indian Nation.

2008a Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from Tumácacori National Historic

Park, Southern Arizona. Report prepared for Tumácacori National Historic Park,

Arizona.

2008b Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from Archaeological Sites South

of Ajo, Arizona. Report prepared for the Bureau of Land Management, Lower

Sonoran Field Office, Phoenix, Arizona.

2008c Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from the International Border,

Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and Wilderness, Southern Arizona. Report

prepared for Northland Research, Inc., Tempe, Arizona.

2008d Source Provenance of Obsidian Artifacts from the International Border,

Tohono O’odahm Nation, Southern Arizona. Report prepared for Northland

Research, Inc., Tempe, Arizona.

Shackley, M.S., F. Goff, and S.G. Dolan

2016 Geologic origin of the source of Bearhead rhyolite (Paliza Canyon)

obsidian, Jemez Mountains, Northern New Mexico. New Mexico Geology 38:52-62.

Skinner, Craig E.

2007a X-Ray Fluorescence

Analysis of Artifact Obsidian from Sonora B:4:503, Sonora B:4:511a, and Sonora

B:4:511b, Sonora, Mexico. Report 2007-41 prepared for the Ajo Chapter of the

Arizona Archaeological Society, Ajo, Arizona, by Northwest Research Obsidian

Studies Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon.

2007b X-Ray Fluorescence

Analysis of Artifact Obsidian from AZ Z:9:46 (ASM), AZ Z:9:52 (ASM), and AZ

Z:9:73 (ASM), Pima County, Arizona. Report 2007-95 prepared for the Ajo Chapter

of the Arizona Archaeological Society, Ajo, Arizona, by Northwest Research

Obsidian Studies Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon.

2007c X-Ray Fluorescence

Analysis of Artifact Obsidian from Sonora B:4:511, Sonora B:4:513, and Sonora

B:4:516, Sonora, Mexico. Report 2007-124 prepared for the Ajo Chapter of the

Arizona Archaeological Society, Ajo, Arizona, by Northwest Research Obsidian

Studies Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon.

Sliva, R. Jane

1997. Introduction to the

Study and Analysis of Flaked stone Artifacts and Lithic Technology. Center

for Desert Archaeology. Tucson.

Tenoria, D., A. Cabral, P. Bosch,

J. Jiménez-Reyes, and S. Bulbulian

1998 Differences in Coloured Obsidians from Sierra de Pachuca, Mexico.

Journal of Archaeological Science 25:229-234.

This page maintained by Steve Shackley

Copyright © 2018 M. Steven

Shackley. All rights reserved.

Revised: 22 August 2024

Back to

the SW obsidian source page.

Back to

the SW obsidian source page.

To the EDXRF Lab home page

To the EDXRF Lab home page