GWYNN AND EWE CANYONS (NEGRITO MOUNTAIN)

WESTERN NEW MEXICO

![]()

Updated 10/3/2013

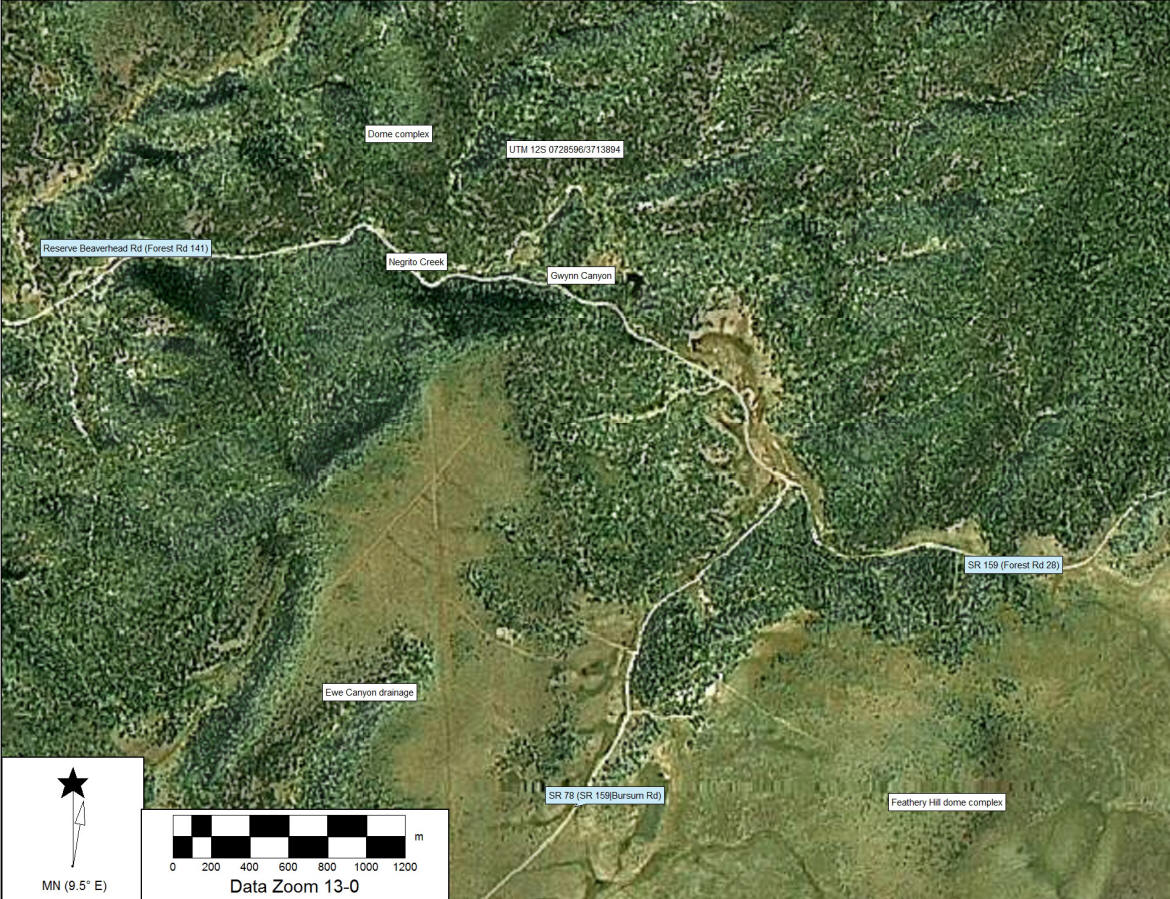

Sections 19,30,31,32 R16W, T9S USGS Telephone Canyon 7.5' Quad; Sections 30,31,32 R16W T9S; Secs. 4.5.9 R16W, T10S USGS Negrito Mtn 7.5' Quad (and see below), Gila National Forest, south central Catron County, New Mexico.

The Gwynn Canyon source was not personally surveyed during the original study. The information and samples used here was provided by Chris Stevenson (then) of New Mexico State University's Obsidian Hydration Laboratory (see also Hughes 1988). The specimens for the original field collection were all procured in Ewe Canyon south of another source area in the Gwynn Canyon area (discovered first; see 2013 collection below). The nodules (at least 5 cm in diameter) are found mainly in a volcanic alluvium and within the washes. The glass is a high quality material, but only 15 nodules were available for study. No specific reduction areas were noted by Stevenson, but most nodules were picked up in the Gwynn Canyon bottom. The 15 nodules studied all have waterworn black cortex and the aphyric glass ranges from an opaque black to a nearly transparent brown. Banding did not occur in this small sample.

There are no known published references on this new source other than the regional geologic map (Weber and Willard 1959).

[updated 1995] In the earlier study (Shackley 1988), this source was not personally mapped or surveyed. My survey in 1993 indicated that marekanites were directly associated with glassy, perlitic rhyolite in Ewe Canyon to the south derived from a dome complex called Feathery Hill on the Telephone Canyon USGS 7.5' Quad. This stream system erodes west toward the San Francisco River. These coalesced domes shown as Feathery Hill on the quadrangle map, exhibit nodule densities in the regolith up to 200 per m2. This locality is located in Sections 19 and 20 T9S R16W Telephone Canyon 7.5' Quad 1963, Catron County, New Mexico. Unmodified marekanites on the domes have maximum diameters near 50 mm, although the vast majority (95%) are 30 mm and smaller. Bipolar cores and flakes were found on and near Feathery Hill, but in low densities (<1 per 100 m2).

As noted above, marekanites are eroding into the Ewe Canyon system and possibly the upper San Francisco River. On March 6, 2019 vitrophyric perlitic obsidian (not artifact quality) nodules were recovered from the San Francisco River alluvium at Glenwood, New Mexico. Two of the analyzed samples matched the Gwynn/Ewe Canyon obsidian source, so artifact quality obsidian from that source potentially enters the San Francisco River system, probably through Negrito Creek into the Tularosa River then the San Francisco River south or Reserve. The pieces recovered in the San Francisco River at Glenwood are certainly derived from the perlite above Negrito Creek at Gwynn Canyon (see map here). Published references for the geology of this source include Findlow and Bolognese (1982:56), the regional geology map by Weber and Willard (1959), and Ratté et al. (1984).

The Gwynn Canyon and two of the Mule Creek groups (Antelope Creek and Mule Mountains) are very similar in trace element composition. Zirconium plotted against Nb, Y, and/or Ba is the best method to discriminate these sources using EDXRF. This can be an important issue in western New Mexico late prehistory because these sources are located in very different environments that may have had cultural significance in prehistory. It is possible that in the late period Gwynn Canyon obsidian could have been controlled by the Cibola branch of the Mogollon while the Mule Creek sources could have been controlled by the Mimbres branch. This may or may not influence the spatial distribution of these obsidian sources in the region and confident source assignment can become crucial. Again, the secondary distribution of Mule Creek is quite extensive to the west through the San Francisco and Gila River systems, and the presence of Mule Creek glass in archaeological contexts to the west may not necessarily indicate that it was procured in the highlands, but could have been procured from the Gila River alluvium (see Shackley 2005). See the Mule Creek page for further discussion here

Table 1. Elemental concentrations for the "original" Gwynn Canyon source standards, and the 2013 sample. Samples GC 11-20 from Feathery Hill at the head of Ewe Canyon, the rest (GC 1-10) are from secondary samples from Gwynn Canyon submitted by Chris Stevenson. All measurements in parts per million (ppm)

|

SAMPLE |

Mn |

Zn |

Rb |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Nb |

Ba |

Pb |

Th |

|

2013 samples |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feathery Hill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

092813-1-1 |

376 |

47 |

208 |

24 |

30 |

145 |

24 |

54 |

27 |

28 |

|

092813-1-2 |

379 |

41 |

215 |

23 |

27 |

139 |

21 |

54 |

26 |

36 |

|

092813-1-3 |

445 |

54 |

235 |

22 |

29 |

151 |

23 |

99 |

31 |

37 |

|

092813-1-4 |

388 |

42 |

211 |

19 |

30 |

150 |

19 |

46 |

27 |

26 |

|

092813-1-5 |

396 |

51 |

222 |

21 |

35 |

149 |

23 |

24 |

28 |

28 |

|

Gwynn Canyon dome |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

092813-2-1-1 |

545 |

38 |

206 |

22 |

31 |

145 |

22 |

63 |

28 |

34 |

|

092813-2-1-2 |

370 |

53 |

218 |

21 |

33 |

140 |

25 |

35 |

27 |

36 |

|

092813-2-1-3 |

466 |

61 |

239 |

24 |

29 |

151 |

21 |

<1 |

36 |

31 |

|

092813-2-1-4 |

406 |

57 |

219 |

20 |

33 |

142 |

19 |

65 |

29 |

32 |

|

092813-2-1-5 |

337 |

53 |

211 |

21 |

28 |

143 |

22 |

39 |

27 |

32 |

|

092813-2-1-6 |

370 |

63 |

209 |

22 |

28 |

150 |

20 |

50 |

30 |

32 |

|

2ndary deposit Gwynn Canyon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

092813-2-2-1 (perlite sample) |

449 |

54 |

227 |

23 |

33 |

154 |

26 |

60 |

28 |

35 |

|

092813-2-2-2 |

453 |

51 |

243 |

25 |

32 |

153 |

23 |

43 |

32 |

33 |

|

092813-2-2-3 |

390 |

53 |

216 |

22 |

30 |

145 |

21 |

60 |

28 |

29 |

|

092813-2-2-4 |

426 |

58 |

221 |

25 |

35 |

145 |

29 |

88 |

31 |

35 |

|

092813-2-2-5 |

348 |

43 |

205 |

21 |

32 |

139 |

25 |

25 |

28 |

25 |

|

0-2813-2-2-6 |

432 |

53 |

227 |

21 |

31 |

144 |

22 |

26 |

23 |

43 |

|

original samples - 1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GC-1 |

418 |

|

237 |

20 |

31 |

161 |

23 |

86 |

|

|

|

GC-2 |

459 |

|

243 |

21 |

30 |

159 |

27 |

85 |

|

|

|

GC-3 |

438 |

|

228 |

19 |

30 |

154 |

22 |

85 |

|

|

|

GC-4 |

414 |

|

216 |

18 |

33 |

153 |

20 |

90 |

|

|

|

GC-5 |

414 |

|

221 |

23 |

32 |

166 |

18 |

94 |

|

|

|

GC-6 |

453 |

|

229 |

19 |

31 |

152 |

26 |

87 |

|

|

|

GC-7 |

454 |

|

237 |

22 |

31 |

155 |

21 |

87 |

|

|

|

GC-8 |

427 |

|

226 |

18 |

31 |

150 |

23 |

86 |

|

|

|

GC-9 |

446 |

|

221 |

17 |

33 |

167 |

21 |

87 |

|

|

|

GC-10 |

417 |

|

220 |

16 |

29 |

151 |

23 |

82 |

|

|

|

GC11 |

420 |

|

231 |

21 |

30 |

158 |

22 |

78 |

|

|

|

GC12 |

508 |

|

244 |

21 |

32 |

164 |

24 |

78 |

|

|

|

GC13 |

460 |

|

237 |

19 |

33 |

156 |

21 |

81 |

|

|

|

GC14 |

363 |

|

196 |

18 |

28 |

137 |

20 |

88 |

|

|

|

GC15 |

376 |

|

223 |

17 |

28 |

151 |

21 |

77 |

|

|

|

GC16 |

415 |

|

230 |

18 |

31 |

158 |

21 |

81 |

|

|

|

GC17 |

501 |

|

243 |

20 |

32 |

162 |

22 |

80 |

|

|

|

GC18 |

328 |

|

198 |

18 |

27 |

144 |

17 |

91 |

|

|

|

GC19 |

456 |

|

227 |

21 |

36 |

163 |

24 |

108 |

|

|

|

GC20 |

414 |

|

222 |

19 |

34 |

150 |

15 |

80 |

|

|

|

RGM1-S4 (USGS) |

273 |

37 |

147 |

106 |

24 |

216 |

8 |

865 |

19 |

17 |

Table 2. Mean and central tendency for the Gwynn and Ewe Canyon samples

|

|

N |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

|

Mn |

37 |

328 |

545 |

420 |

47 |

|

Fe |

37 |

7368 |

10860 |

8980 |

782 |

|

Zn |

17 |

38 |

63 |

51 |

7 |

|

Rb |

37 |

196 |

244 |

223 |

13 |

|

Sr |

37 |

16 |

25 |

21 |

2 |

|

Y |

37 |

27 |

36 |

31 |

2 |

|

Zr |

37 |

137 |

167 |

151 |

8 |

|

Nb |

37 |

15 |

29 |

22 |

3 |

|

Pb |

17 |

23 |

36 |

29 |

3 |

|

Th |

17 |

25 |

43 |

32 |

5 |

Table 3. Oxide values for one sample from dome complex in Gwynn Canyon (see map below)

|

Sample |

SiO2 |

Al2O3 |

CaO |

Fe2O3 |

K2O |

MgO |

MnO |

Na2O |

TiO2 |

|

092813-2-2-2 |

75.709 |

11.375 |

0.608 |

1.265 |

6.037 |

0 |

0.094 |

4.456 |

0.206 |

|

RGM1-S4 |

74.501 |

12.051 |

1.505 |

2.294 |

5.182 |

0 |

0.053 |

3.874 |

0.293 |

Sr, Rb, and Zr concentration plot of the Gwynn Canyon and Mule Creek sources. Note the genetic similarity.

Survey and collection, 28 September 2013 with Jeff Ferguson.

On this date Jeff Ferguson and I re-surveyed the Gwynn/Ewe Canyon area and Feathery Hill and collected more samples. The location and general character of the Feathery Hill locality eroding into Ewe Canyon was confirmed, but another locality to the northwest above Negrito Creek in Gwynn Canyon was located that produced artifact quality marekanites. Initial survey of Gwynn Canyon above this locality at UTM 12S 0728596/3713894 ± 3m, indicated that no obsidian was present in Gwynn Canyon. Below the above noted locality however, abundant marekanites are entering Negrito Creek in Gwynn Canyon and possibly eroding into upper San Francisco River. This locality is a dome complex consisting of perlitic lava near the military crest of the domes with a thin lahar below. While no marekanites were found in-situ in the perlite, there were marekanites in the perlitic sand eroding directly from the perlitic lava. The marekanites up to about 30 mm down to pea size were found in a small wash eroding into Negrito Creek. The Feathery Hill obsidian erodes south through Ewe Canyon, while the obsidian in Gwynn Canyon is eroding west through Negrito Creek potentially into the San Francisco River system (see map below).

The elemental composition between these localities is similar (see Tables 1 and 2). A perlite sample analyzed from the dome complex on the north side of Gwynn Canyon is well within the range of variability indicating that the marekanites recovered are from the same magma source, although none were located in-situ.

The 2013 collection also expanded the character (opacity, sphericity) of these marekanites at the source. All of the marekanites from both localities are sub-rounded. A few of the samples from Feathery Hill are entirely mahogany to black/mahogany, not seen in the earlier collections or noticed in the archaeological record. The character varies from nearly opaque black to nearly transparent with black banding. There is no detectable elemental differences between colors.

References

Findlow, F.J., and M. Bolognese, 1982, A preliminary analysis of prehistoric obsidian use within the Mogollon area. In P.H. Beckett (Ed.) Mogollon Archaeology: Proceedings of the 1980 Mogollon Conference, pp. 297-316. Ramona, California: Acoma Press.

Hughes, R.E., 1988, Archaeological significance of geochemical contrasts among southwestern New Mexico obsidians. Texas Journal of Science 40:297-307.

Ratté, J.C., R.F. Marvin, and C.W. Naeser, 1984, Calderas and ash flow tuffs of the Mogollon Mountains, southwestern New Mexico. Journal of Geophysical Research 89:87113-8732.

Shackley, M.S., 1988, Sources of archaeological obsidian in the Southwest: an archaeological, petrological, and geochemical study. American Antiquity 53:752-772.

Shackley, M.S., 2005, Obsidian: Geology and Archaeology in the North American Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Weber, R.H., and M.E. Willard, 1959, Reconnaissance geologic map of Mogollon 30 minute quadrangle. New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro.

![]()

This page maintained by Steve Shackley (shackley@berkeley.edu).

Copyright © 2013 M. Steven Shackley. All rights reserved.

Revised: 27 March 2019

![]() Back to

the SW obsidian source page

Back to

the SW obsidian source page

![]()